Dragon Fruit Data Analysis

The purpose of this page is to see if there is any correlation between weather conditions and dragon fruit budding and flowering. This could give growers a better insight into what care is required throughout each part of the season to maximise production. To do this, I recorded the number of dragon fruit flowers that opened each night for four consecutive seasons (across a six-month period), from 2020-21 to 2023-24. While buds are closer to any potential causes, they can be difficult to spot when they first appear and some of them will inevitably abort if there is a large flush. The opening of flowers (which do so for only one night) can be recorded with perfect accuracy, and I reasoned that tracing the data back by three weeks would yield a reasonable representation of bud appearance, as this is the typical time from bud to flower opening. Going back a little further might reveal possible causes, such as an increase in temperature or dryness. Further, there is the possibility that dragon fruit plants can somewhat “predict” the weather around the time of flower opening, so perhaps they bud such that there is a drop in the temperature or an increase in rainfall in a few weeks’ time. All these things can be tested with the recording of flower openings.

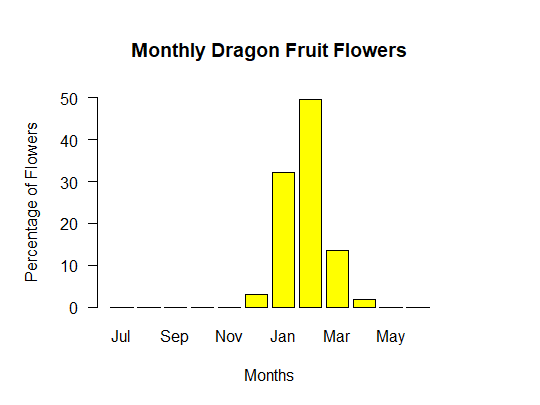

The graph to the left (or above, depending on your device) gives you an idea of what my fruiting season looks like – it displays the average number of flowers each month over the four seasons I recorded flower openings. I live in Perth, Western Australia, which is in the southern hemisphere, so winter goes from June to August with the winter solstice on June 21, spring from September to November, summer from December to February with the summer solstice on December 21, and autumn from March to May. During winter, my dragon fruit plants grow very slowly, but do not have to face any frost due to my location. However, cactus rust does seem to spread during this time. When it begins to warm up in spring, my dragon fruit plants come back to life putting on lots of new growth before they begin fruit production in late spring/early summer. As you can see, my earliest dragon fruit flowers occur around November and the latest around April, with the most flowers occurring during the summer period. The hot weather seems to get rid of the cactus rust and many of the bugs that arrive in spring, and the plants appear much healthier so long as they are protected from the sun and are well-watered and fertilised.

Whatever the season, I cannot control the weather. However, I can control the amount of water, fertiliser, shading, and pruning I give my dragon fruit plants, as well as when I do these things. Hopefully the following analysis provides some insight into the correlation between dragon fruit flowering and the weather, so the factors we can change can be controlled accordingly to try and extend the dragon fruit season both ways. I will be focussing on temperature, solar exposure, and rain, with a quick look at moon phases to see if this is more than an urban myth. Please note there are countless other factors that could affect dragon fruit budding and fruiting, but these are the things I can easily find data for. There is also the possibility that budding is mostly a response to when I put out potash, though clearly this only works in the right season so there must be some element of the weather contributing as well. Variety also plays a major part, with some varieties – notably Sugar Dragon – budding long before others, but this too is season-dependent. All weather data was taken from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology Website, and the data for the moon phases was taken from the Perth Observatory and converted into a sinusoidal wave by myself.

Method of Analysis

The data was taken across the six-month period of November 1 to April 30. I chose to represent it in two formats: graphically to get a “feel” for any possible trends, and in table format to allow for some additional analysis and to put numbers behind any possible trends. The graphs are hopefully reasonably intuitive, and the season can be switched by clicking the respective buttons above the graphs. The tables require a little more explanation. There is one for each season, each summarising the data from its four corresponding graphs. The row-headings “max” and “min” refer to the daily maximum and minimum temperatures (in degrees C), “solar” to the daily solar exposure (in MJ/m^2), “rain” to the daily rainfall (in mm), and “moon” to the daily phase of the moon, with “0” corresponding to a new moon and “1” corresponding to a full moon. The first column, “avg”, is simply the average of each of these quantities across the six-month period, with the moon phase average fixed at 0.5. While this provides a nice baseline for comparison, it makes its way into the cooler and wetter seasons which naturally distorts some of the values, which is why I have highlighted them in green. The second column, “w_avg”, refers to the weighted average of the weather condition based on the number of flowers each day. The third column, “fw_avg”, refers to the weighted average of the weather conditions the week before each flower. The fourth column, “bw_avg”, refers to the weighted average of the weather conditions approximately one week before each bud (from four to three weeks before opening). Values highlight in yellow are the highest in their row, disregarding the first column, with the hope of making any patterns easier to spot.

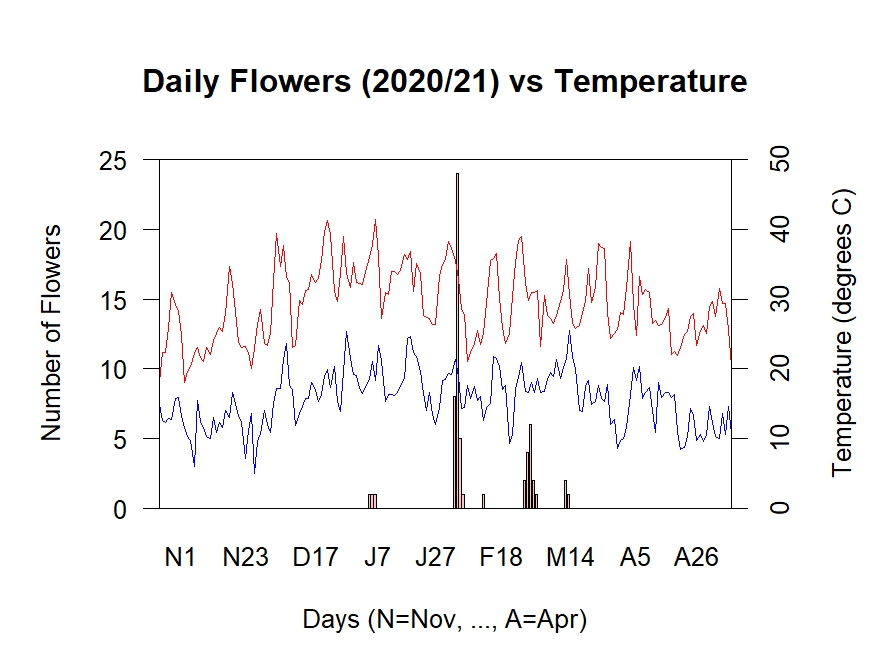

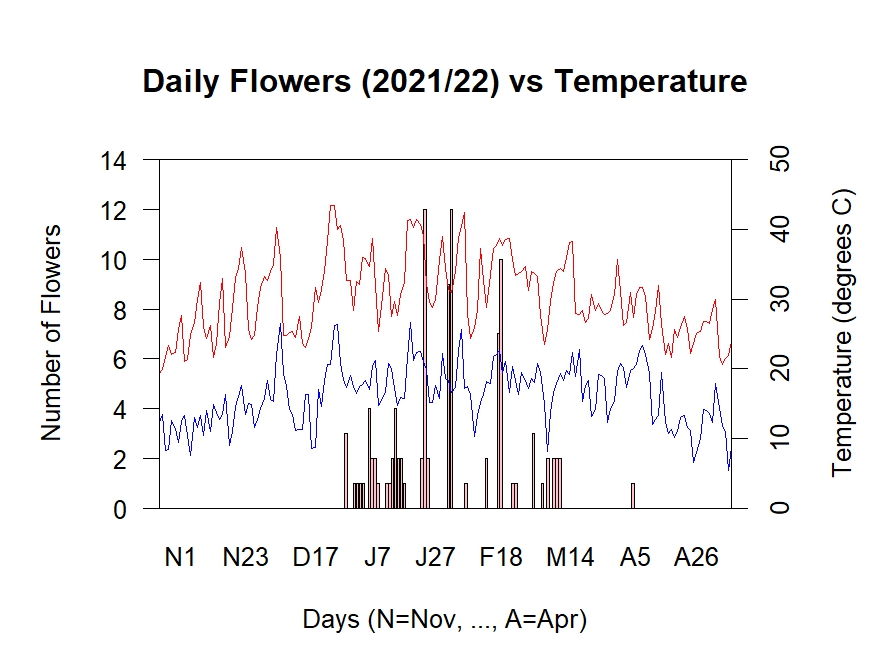

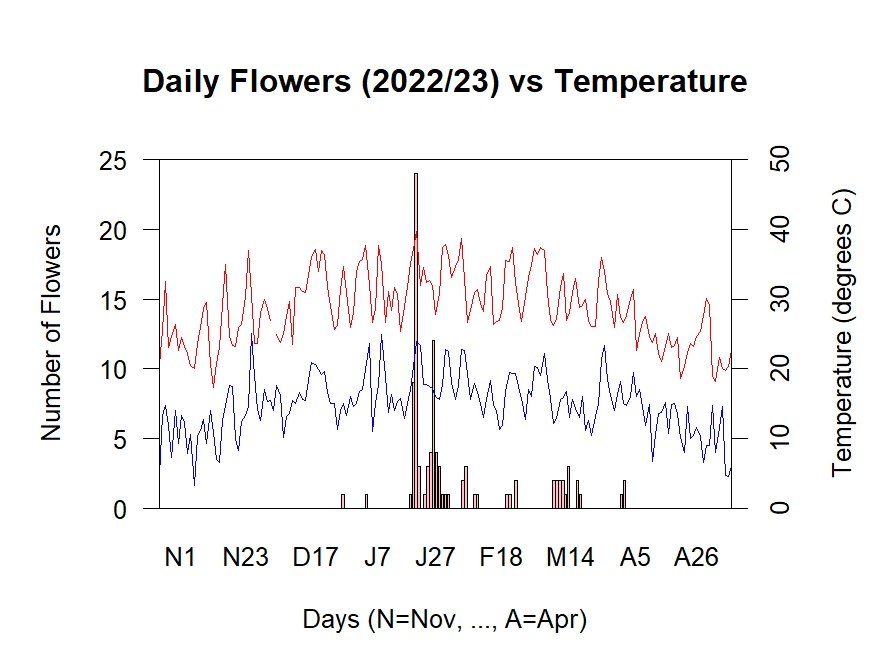

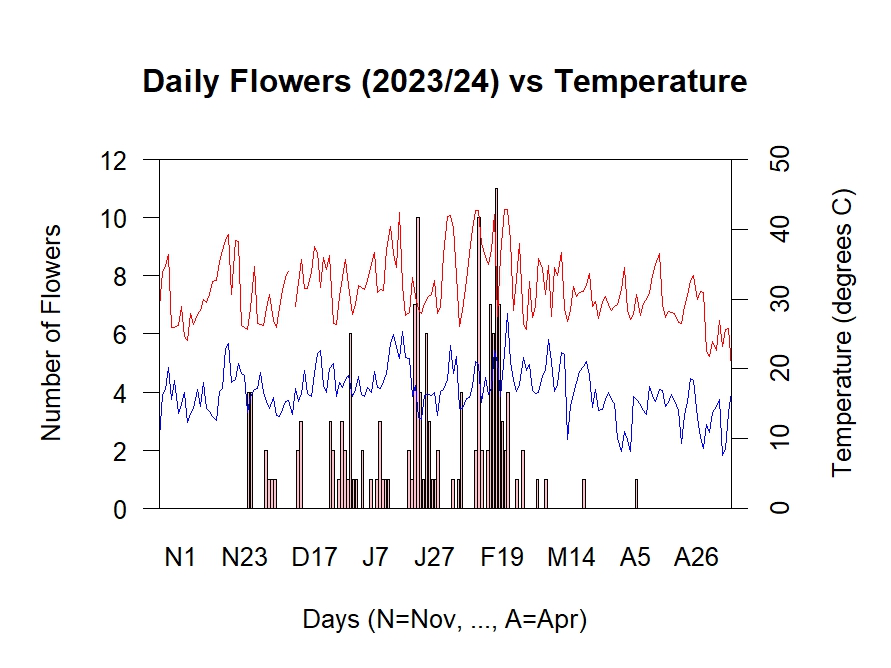

Flowers vs Temperature

Other than more flowers during the warmer times of the year, there doesn’t appear to be a direct correlation between dragon fruit flowers and temperature. This is probably because temperature is a measure of the average kinetic energy of particles, not the amount of sunlight received (which could potentially lead to more photosynthesis and thus more energy for bud production). If anything, the temperature seems to drop a little before the formation of buds, which is evident in the latter three seasons. If there is anything to this, I’d suspect that perhaps when the plants are given a bit of respite, they have more energy reserves to produce buds. However, this seems contradictory when I consider that often buds seem to appear as a response to stress, such as mild sun burn or pruning. Perhaps further study could enlighten the situation, but as you’ll see solar exposure seems to offer a much better insight than temperature, and negates the “respite” theory.

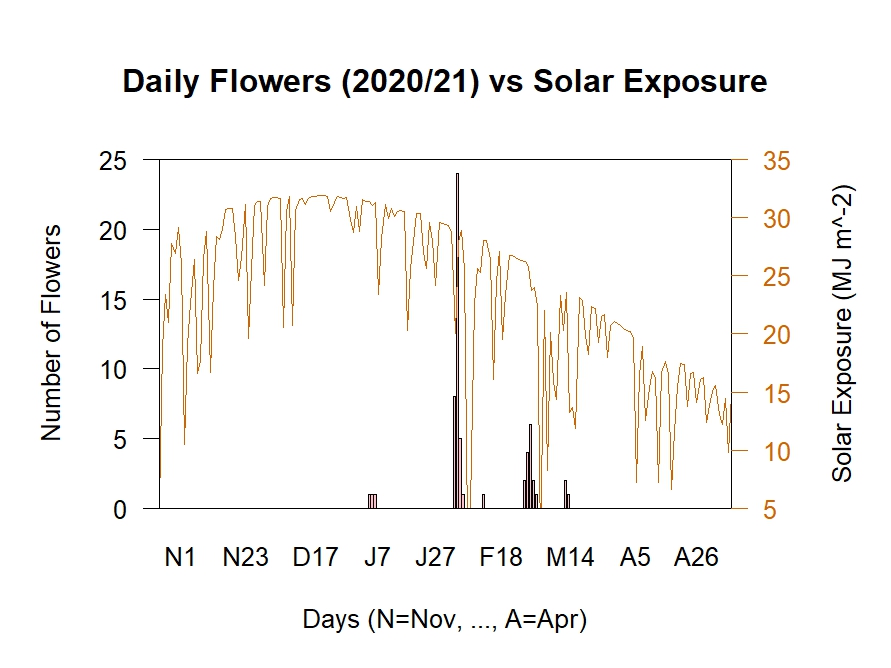

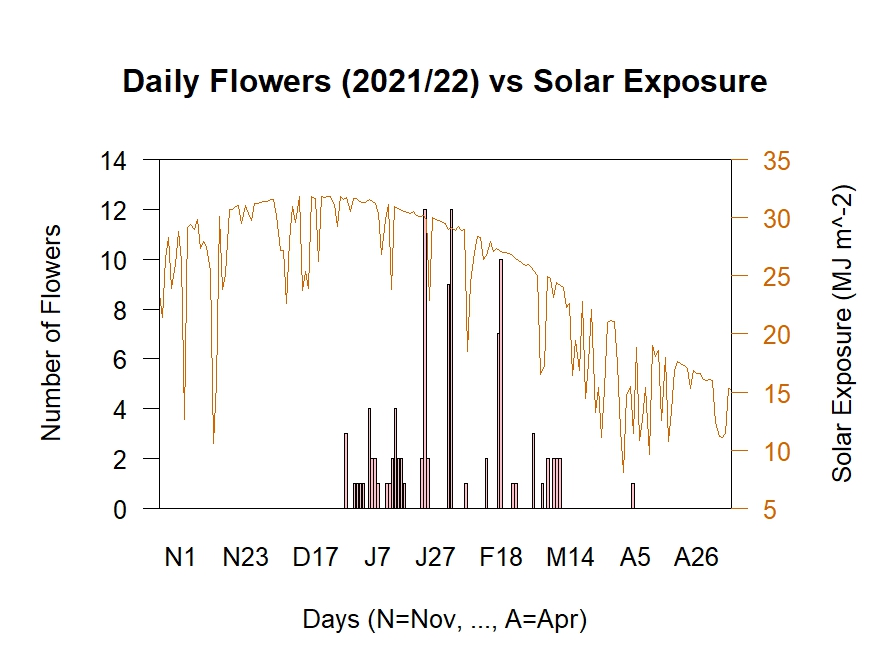

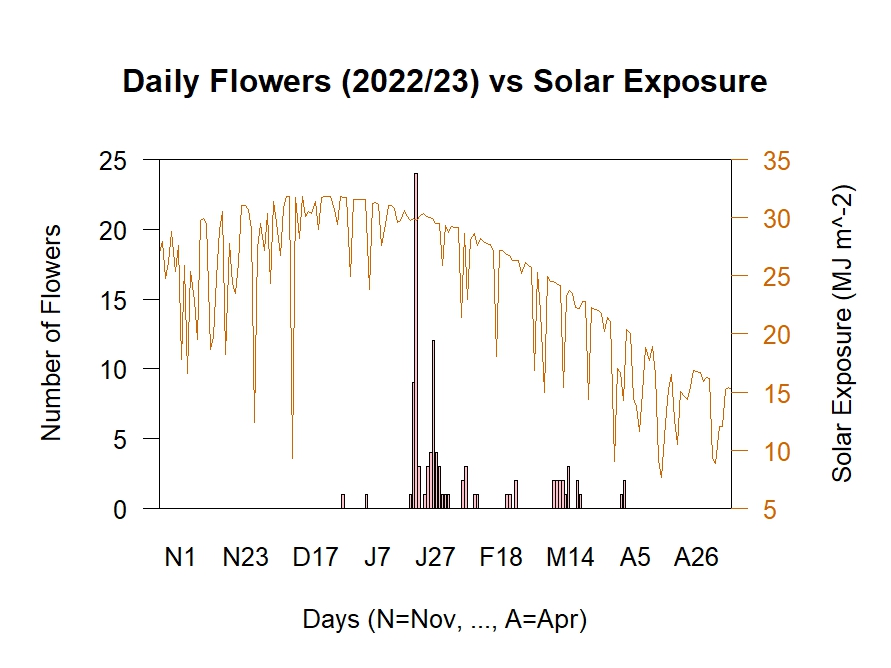

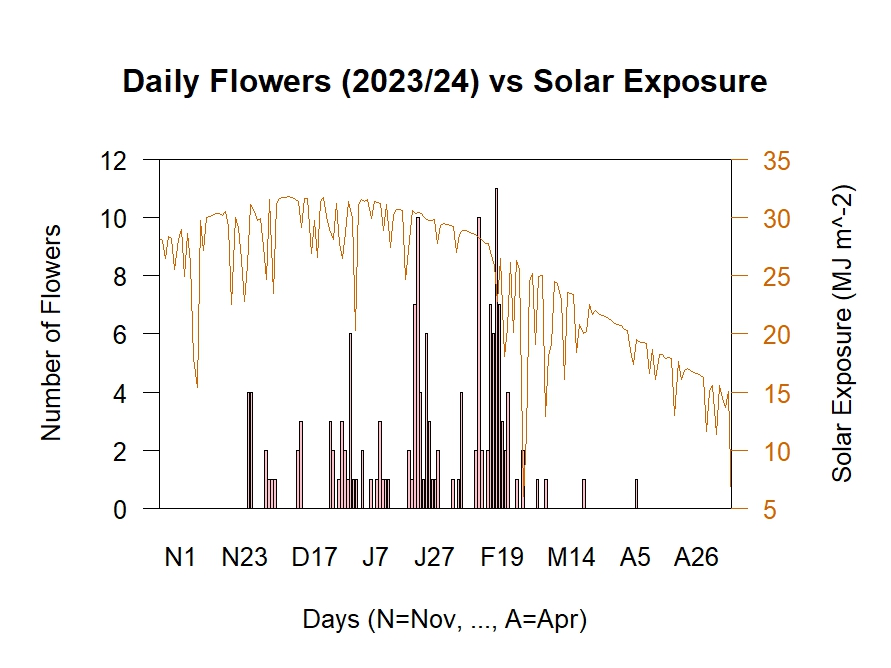

Flowers vs Solar Exposure

There appears to be a consensus that dragon fruit budding is linked to the amount of sunlight hours received each day, so much so that some farms put up lights to extend the fruiting season. Solar exposure is closely linked to sunlight hours, measuring the amount of the Sun’s energy that reaches the surface per unit area. This last part is important, because unlike temperature, which is not concerned with cloud cover, solar exposure is an accurate representation of how much energy each plant is receiving (not just “feeling”) on a given day. Solar exposure has by far the most obvious trend in my data, and the trend is identical across all four seasons. The week preceding bud formation experiences measurably higher solar exposure than the week preceding flower opening, which experiences measurably higher solar exposure than the day of the flower opening itself. You can clearly see this drop on some of the graphs. This suggests that perhaps budding is triggered by an increase in solar exposure, which is interesting if we consider temperature might have suggested otherwise, though the two are certainly not equivalent. In any case, solar exposure is the more important condition as it considers cloud cover, and this could account for the difference. It also leaves open the possibility that dragon fruit plants can “predict” a decrease in solar exposure around the time of flowering, perhaps even on the day of flowering, which makes sense given that flowering takes a lot of energy. Of course, correlation does not mean causation, and looking at the graphs, solar exposure appears a little less “random” than temperature in that it naturally follows a bit of a curve, peaking around the summer solstice. But the large dips could easily throw the trend off somewhere across the four seasons, and this curve might be part of the cause anyway. Maybe the summer solstice is the cause of the biggest flush of buds. Regardless, it is safe to say there is a strong indication that solar exposure is linked to budding and flowering.

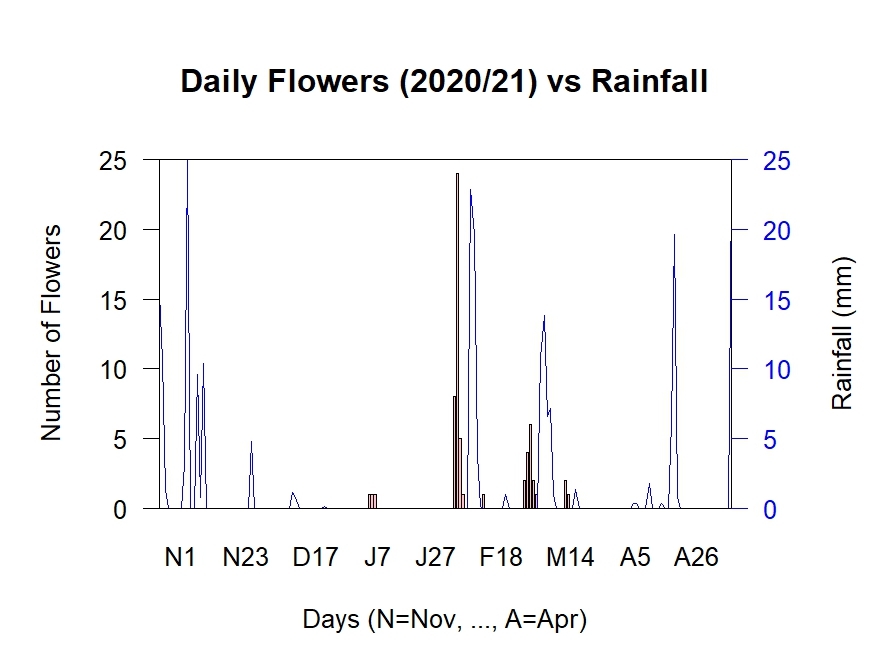

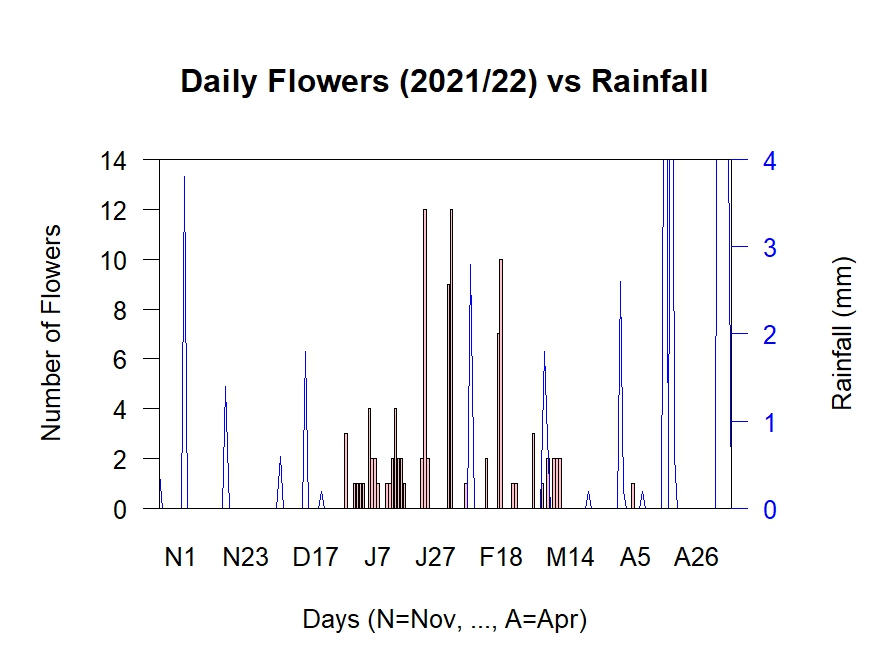

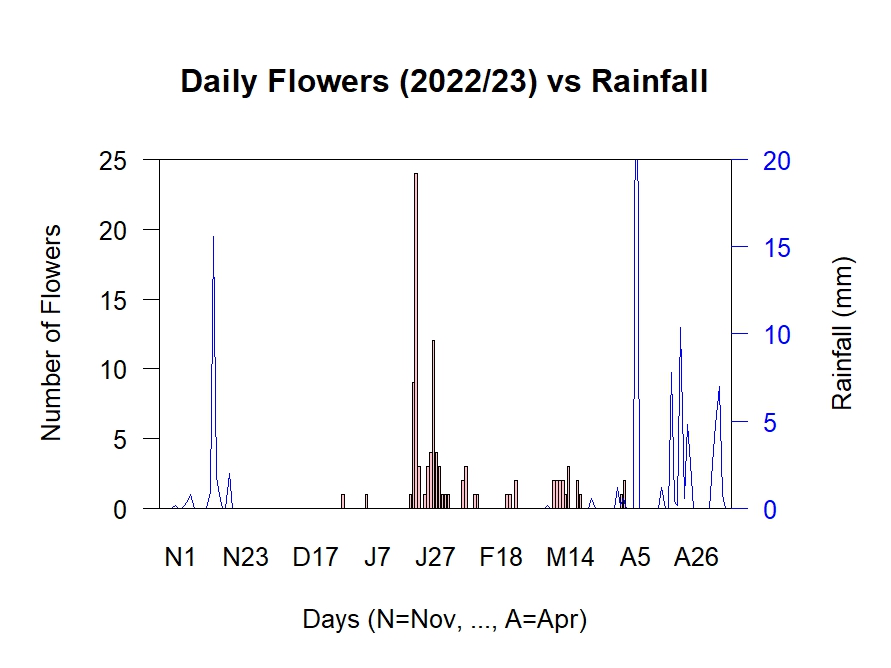

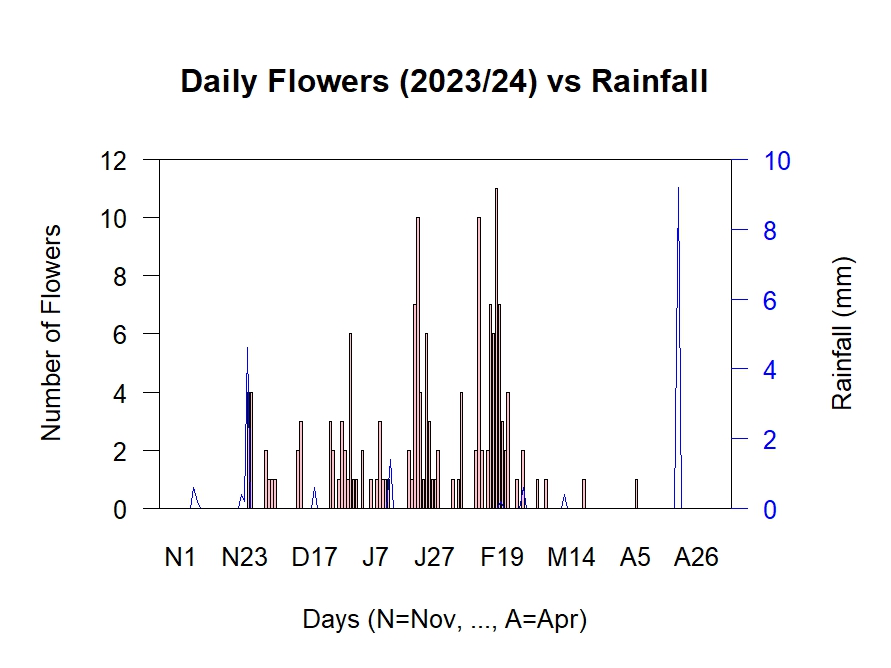

Flowers vs Rain

While the graph of the season 2020/21 may look incredibly promising, with rain fitting the flowering cycle almost perfectly with a slight lag, this was not the case for the other seasons. In fact, I find it very difficult to discern any pattern at all, particularly after tabulating the data. It seems that rain is as unpredictable as the forecasters (unknowingly) demonstrate, and this is complicated further when my hand-watering is considered. It would not be unlikely that my dragon fruit plants interpret this as “rain”, though of course this could not be predicted like, potentially, the water direct from the clouds. Another issue with using rainfall for my analysis is that Perth just doesn’t rain very much over the summer period. It seems unlikely that flowers would wait out until the usually very minimal and spaced-out periods of rainfall. Perhaps if this study was conducted in a more tropical area, a correlation might start to appear. But of course, its seemingly random nature might render the same results. In any case, if it can’t be easily predicted then it’s not much use in dictating how I care for my dragon fruit plants, particularly over the length of an entire season.

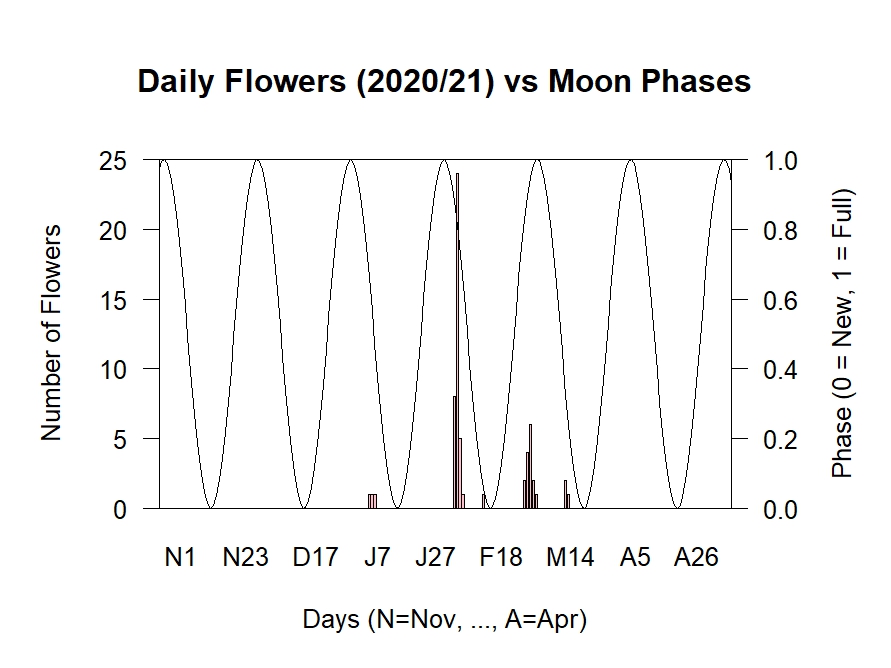

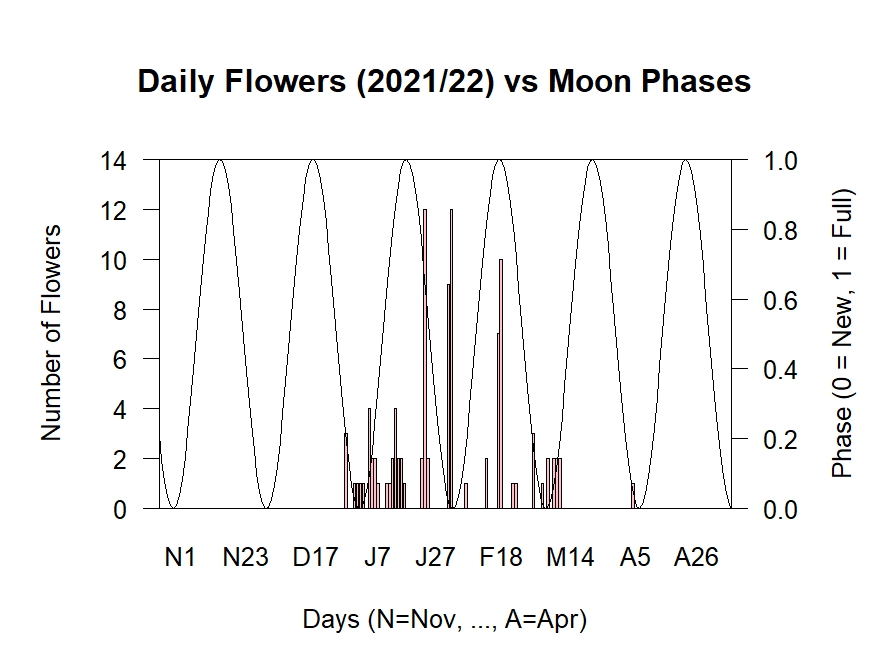

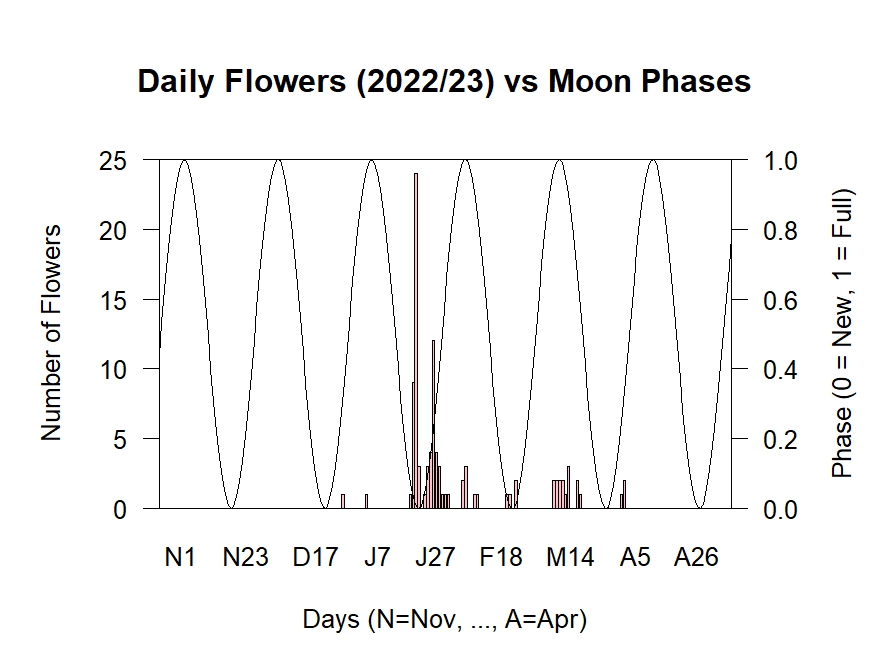

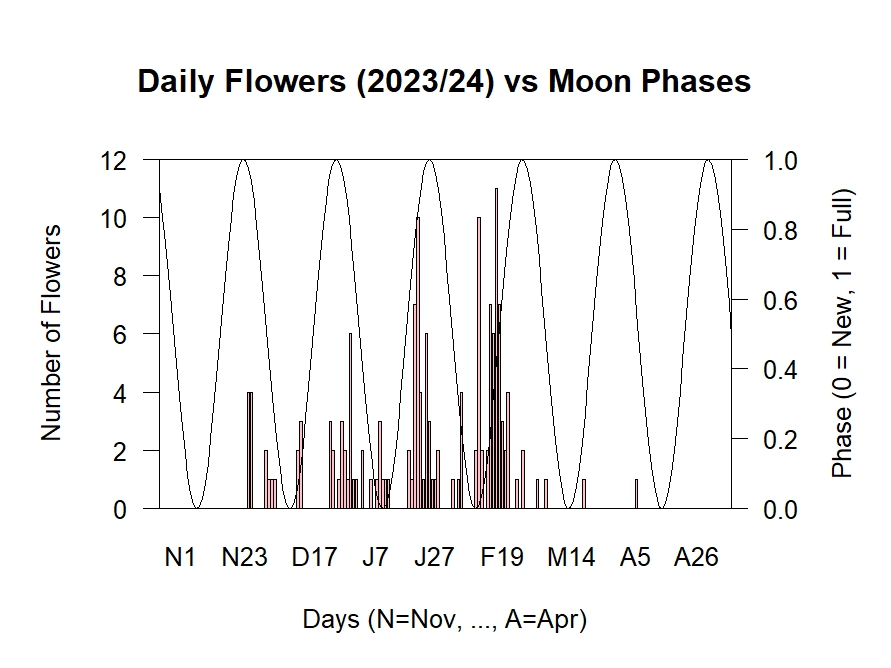

Flowers vs Moon Phases

There seems to be a notion going around that dragon fruit flowers usually open around a full moon, perhaps due to the increase in nocturnal pollinators with the extra light. While this may be true for some species of cacti (see here), I couldn’t find any direct evidence for dragon fruit, so I was interested to have a look myself. Like rainfall, the 2020-21 graph looks promising, with flowers fitting inside the “moon wave”. However, the other seasons do not show the same trends, and the tabulated data is even less clear, with some of the data points above and some below the standard average of 0.5. Even if there was some faint link between flowering and the lunar cycle, it seems unlikely that it would hold much of a bearing against other more obvious weather conditions. As such, I am confident that there appears to be no correlation between dragon fruit flowering and moon phases, so it would be best to focus on other areas for maximising production.

Conclusion

I often spot dragon fruit plants in the neighbourhood that flower on the same night as mine, subject to different fertilising and watering schedules, different positioning and shading. Could certain weather conditions play a role in this? Of course, I have only done the very basics in analysing the trends between dragon fruit budding and flowering and corresponding weather conditions, but there is at least one significant conclusion that can be drawn. This conclusion is that solar exposure is more important than temperature as an environmental stimulus. For so long, I have let temperature dictate the amount of water, fertiliser, and shade I give my dragon fruit plants, but perhaps it would have been better if I gave the reins to solar exposure. However, this is easier said than done. Daily solar exposure forecasts are not as easily obtainable as daily temperature forecasts, and it would take time to build up an intuition behind the values. Most people already have this intuition with temperature, and know (if you use the metric system) that 20-30 degrees C is mild, 30-35 degrees C is rather hot, and 35-40+ degrees C is quite awful. What about 7,694 W/m^2, the predicted value on the day of writing? Perhaps this intuition is worth building, however, considering the consistency of the trend: high solar exposure before budding, then reduced solar exposure through to a low on the day of flowering. It may even be worth fitting your fertilising schedule around the summer solstice which is typically the period of highest solar exposure. The other things I tested – rainfall and moon phases – seemed to have no correlation with dragon fruit budding and flowering and probably don’t need as much consideration. However, there may be other weather conditions that have an effect. I didn’t test humidity, pressure, or wind, and I only tested in one location. There are so many variables, both weather-related and not weather-related, that could affect dragon fruit budding and fruiting. But if we can find the major contributors, we can leverage this to maximise production. In any case, I hope fellow dragon fruit enthusiasts find this page interesting and useful.